"Heritage Flats" is a 10-story affordable housing tower proposed by local developer Mark Vengroff, who submitted an unsolicited bid to develop the property on a lot owned by the City of Sarasota. | Image from Vengroff's bid

A bold affordable housing plan sputtered. Now Sarasota is trying again

Nearly two years ago, Sarasota’s then-City Manager Marlon Brown had an ambitious idea to purchase downtown property near City Hall and turn it into large-scale affordable housing.

In an effort that would become the first-of-its-kind across Florida, Brown secured millions of dollars in pledges from the area’s largest philanthropic foundations and millions more earmarked from the Florida Legislature.

The blueprint promised to tackle one of downtown Sarasota’s most pressing problems — a lack of affordable housing in the urban core that has long become a playground for the wealthy.

With the support of city commissioners, Brown’s plan would see the city take direct control over the development, own the property and supply nearly 200 units of attainable housing in two high-rise buildings on First Street, with a groundbreaking anticipated in mid-2025.

It was uncharted territory in Sarasota. Development of affordable housing is typically done on less expensive land facilitated with complicated financing that often requires tax credits. Instead of high-rise development, these projects are typically not more than three or four stories — an exception being Lofts on Lemon, which is five stories — and involve partnerships with developers that have decades of experience in the highly regulated industry.

Even then, deals can take years to go from plans on paper to shovels in the ground. What Brown proposed would speed up the timeline, deliver more units and keep the city in full control along the way.

Sarasota spent more than $7 million on two parcels in September 2024.

A month later, Brown resigned. The anticipated groundbreaking never happened. Promised foundation dollars never materialized. And the project seemingly languished as Sarasota cycled through two interim city managers.

But it is now stirring again.

Sarasota purchased property across the street from City Hall. | Photo by Derek Gilliam, Suncoast Searchlight

Days after Suncoast Searchlight started asking questions about the status of the project, the city issued a request for proposals — on Jan. 27 — for an outside consultant to find a development partner.

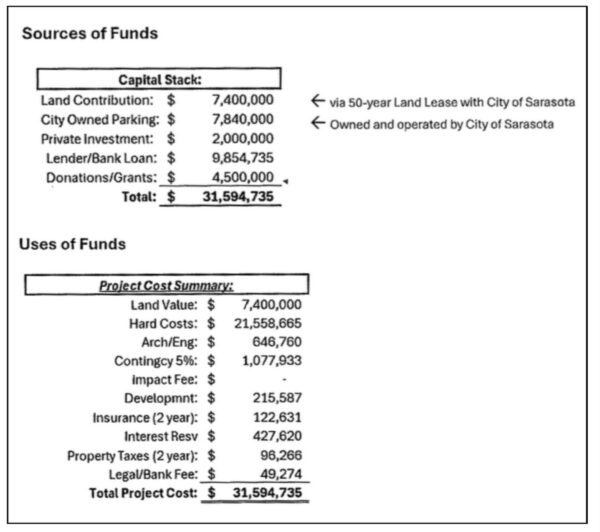

The same week, the city received an unsolicited bid from local developer Mark Vengroff to build 75 units of affordable housing on the site that would all be rented to individuals earning at or below 80% of the area median income — the income bracket housing experts say is most lacking. The total project cost: $31.6 million.

When asked about his unsolicited proposal, Vengroff told Suncoast Searchlight that he was “asked by multiple parties to submit a bid for this project” but declined to name them.

The bid, backed by three major local foundations, asks the city to chip in nearly $8 million more.

Details surrounding Vengroff’s proposal — including the feasibility of his project cost, and whether the city will rush into another plan without proper due diligence — has raised questions from real estate experts and city advocates who fear a repeat of the first sputtered attempt.

“This thing has sat there suspended for so long, it’s hard to recollect what’s really going on,” Commissioner Kyle Battie said. “I’m still kind of hopeful about the project, about us getting some affordable housing in the downtown area, because I think the downtown should be a diverse, eclectic area that everyone can live, work and play in and enjoy. Not just for those that have money.”

The new proposal answers some of those questions but raises others.

Vengroff, who has never built a high-rise tower, is proposing a 10-story building with retail space on the ground floor, four floors of parking and five floors of affordable housing — a mix of studios, one-bedroom and two-bedroom apartments. Seventy-five units in all. If the first phase moves forward, a second tower with an additional 75 units could follow.

Vengroff’s submission also cites construction costs that are far lower than the figures previously floated by the city — a claim that housing and real estate experts say warrants further scrutiny.

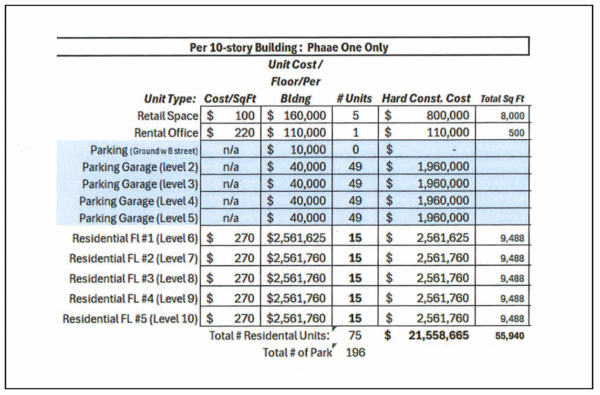

The total project cost includes the land value, architectural and engineering services, insurance and other fees. The majority of the cost — $21.5 million — would go toward construction.

The “hard construction” cost breakdown for the project includes the price for each floor of the proposed 10-story building. The floors of parking (in blue) would be paid for by the city, according to the plan submitted by developer Mark Vengroff. | Image from Vengroff’s bid

“His cost per unit is $170,775 per unit. That is impossible,” said Jack Dougherty, a prominent Pinellas County developer who has built multiple apartment towers in St. Petersburg, wrote in an email to Suncoast Searchlight.

In an interview with Suncoast Searchlight this week, Vengroff brushed aside skepticism of his ability to deliver on his proposal, pointing to past developments that faced similar doubt.

“No one said that we would be able to build the Nest Apartments in Bradenton at the price we told (the) Manatee County government,” he said. “We are finishing that project now at $135 per square foot.”

His proposal has received the backing of the three foundations that originally pledged $4.5 million toward the city’s land purchase. Their contribution would now offset construction instead.

Current city leadership received the proposal last week and are still determining how they will respond.

Jon Thaxton, Gulf Coast Community Foundation’s director of policy and advocacy, partnered early with Brown on the project and convened other area foundations to join in. He remains hopeful in the project’s potential.

“It shouldn’t come as a surprise to anyone that the city manager position being in flux with three different individuals over the past two years has been a deterrent to progress,” Thaxton said. “It’s obviously taking more time than what was originally proposed.”

Sarasota’s ambition outpaced its planning

The push for a city-led housing development did not begin with a detailed financial plan.

It began with a question raised by then-City Commissioner Erik Arroyo at a January 2023 city workshop: If the private market was not producing enough affordable housing, why shouldn’t the city try to do it?

A needs assessment cited in the latest proposal estimates Sarasota County will require roughly 8,200 more affordable units within the next decade to keep pace with demand. But only about 900 are currently in the construction pipeline, highlighting a gap that housing advocates say the private market has consistently failed to fill.

Brown embraced Arroyo’s idea and began moving quickly.

By March that same year, he won commission approval to hire a broker to find suitable land for the project, and early on, focused on a specific location — a city-owned parking lot across from City Hall and three privately owned parcels immediately east.

Two parcels purchased by the City of Sarasota (light blue) on First Street across from City Hall are slated for affordable housing. The city already owned a parking lot (dark blue) but was unable to acquire the middle parcel and an office building owned by 1st Street Credit Union (red). | Graphic by Suncoast Searchlight using Sarasota County Property Appraiser GIS map

Although none of the parcels were listed for sale, the broker began negotiating with the owners. At the same time, Brown worked to line up outside support. By the time he returned to commissioners in April 2024, he had contracts to purchase two of the three parcels, along with partial commitments from three major philanthropic foundations and the state Legislature to cover $6.5 million of the $7.4 million price tag.

The city’s share, he told commissioners, would amount to less than $1 million.

Once it secured the land, Brown said, the city would clear the lots and build a pair of 12-story towers boasting a combined 192 units — eight of which serve low-income renters, or those earning at or below 80% the area’s median income. The rest would be reserved for those earning between 80-120% AMI, a population Brown characterized as “workforce” renters.

What he did not present was a comprehensive business plan or construction budget.

Steve Horn, Ian Black, Marlon Brown and Chris Gallagher (of Hoyt Architects) answered questions from city commissioners during the an April 15, 2024, meeting. The City Commission unanimously voted to move forward with buying the 1st Street properties after the discussion. | Image from City of Sarasota video

During public comment, several critics warned that the city was barreling toward a complex real estate venture without understanding the cost or how it would be financed. One resident, John Harshman, a Sarasota commercial real estate broker who recently filed to run for the city commission, urged commissioners to get a breakdown of funding sources before moving forward.

Another resident, Jose Fernandez, a retired Union Carbide executive, held up a piece of paper filled with blanks where costs should be and told commissioners: “If you approve this, it’s tantamount to writing a blank check from the people’s account.”

The city moved forward anyway.

“Stop saying you want it (affordable housing), but don’t want to do anything about it,” said Battie, who represents the historically Black Newtown neighborhood, pushing back on the criticism.

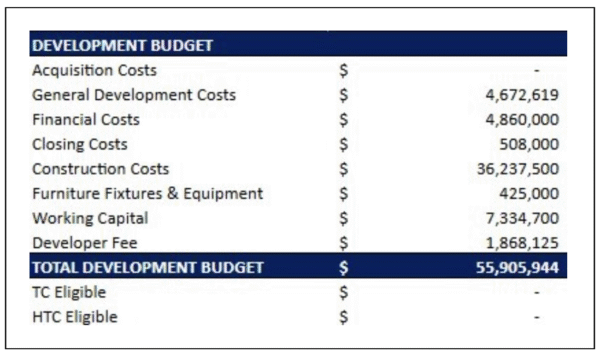

Only months later did a written pro forma surface. Prepared by Steve Horn of Ian Black Real Estate, the city’s broker, the plan showed a single 12-story tower with 124 units and a total development budget of $55.9 million. Of that amount, $36.2 million would be for construction.

Based on projected rents, the city could support roughly $27 million in borrowing, leaving a financing gap of about $30 million for the first building alone.

There was no financial plan done on a second tower. But the city had sent out a press release after the commission vote announcing the full 192-unit project and saying construction costs would be $70-$80 million.

The pro forma for the city’s proposed affordable housing project estimated the entire development would cost nearly $56 million, with about $36 million of it funding construction alone. | Image from the city’s pro forma

Only Commissioner Jen Ahearn-Koch said she received the pro forma after it was completed — and only because she asked for it. She received it on Sept. 16, 2024, the day the city closed the deal with the property owners. Other commissioners told Suncoast Searchlight they do not recall seeing the document or being briefed on the $30 million funding gap. By then, though, it was too late. They had already authorized the purchases and drained the city’s Affordable Housing Fund to come up with the money.

The city footed the entire purchase price. Gov. Ron DeSantis had vetoed the $2 million in state funding proposed by local legislator State Rep. Fiona McFarland (R-Sarasota), and the foundations did not provide the $4.5 million that Brown had negotiated.

One month after closing on the properties, Brown quit his job, telling Suncoast Searchlight it was for health reasons. He started a new job with the Sarasota Chamber of Commerce as their director of government affairs a few months later.

Brown told Suncoast Searchlight he still believes in his vision.

“I would love to see it,” he told reporters. “If it doesn’t happen, would I lose sleep over it? No.”

After the purchase, a long stall

Following the purchase of the properties in September and the departure of Brown in October, the “Attainable Workforce Housing Project” seemingly stalled, with little, if any, public discussion in 15 months.

Behind the scenes, however, negotiations with the foundations continued. In May, eight months after leaving the city, Brown was tapped to negotiate the foundations’ contributions toward the project. But he told Suncoast Searchlight that he later passed that responsibility off to Chamber President and CEO Heather Kasten.

But things unraveled sometime after that, when Interim City Manager Dave Bullock walked away from the money over a proposed donor agreement whose terms he said were too risky at the time.

In order to get $1.5 million from each foundation toward the cost of the property purchase, the deal required the city to break ground on an affordable housing project by the end of 2026, commit to all units being rented to people earning below 120% area median income and keep the property for at least 10 years or else return the money with interest.

Now the three foundations — Charles & Margery Barancik Foundation, Community Foundation of Sarasota County and the Gulf Coast Community Foundation — have since pledged those same dollars to Vengroff instead. The funds would go toward construction, with a development agreement promising units for renters earning at or below 60-80% of the area median income.

(Suncoast Searchlight has received grants from Barancik Foundation and Gulf Coast Community Foundation to fund newsroom operations.)

The unsolicited proposal from Harvey Vengroff included the backing of at least three local foundations. | Image from Vengroff’s bid

Representatives from all three foundations told Suncoast Searchlight their priority is to generate the maximum number of affordable housing units, a desire shared by Ahearn-Koch :“If the city is going out on a ledge, then we should only focus on investing in a project with units that are serving an 80% AMI and below demographic.”

But the city has no experience in real estate development, Bullock told Suncoast Searchlight, which is why he issued the RFP last week for a consultant.

“When you see a project that will never move forward, you identify the foundational weaknesses, then retool and try to see how you can meet the Commission’s objectives,” Bullock told Suncoast Searchlight. “We have no background in mixed-use, commercial residential development. I backed up and said we need help to put this deal together. Commission objectives must be grounded in actual understanding of how things work.”

Bullock told Suncoast Searchlight that he is now reviewing the new Vengroff proposal and working with the city attorney to determine if it meets the proper criteria.

“If this moves lightning fast, you’re two to three years out from breaking ground,” Bullock told reporters last week.

A new proposal enters the picture

Vengroff, whose father Harvey Vengroff became one of the region’s largest affordable housing providers in the 1990s, also has his own track record of bringing similar projects to life by converting motels into affordable units throughout Florida and Tennessee.

His company, One Stop Housing, has a pipeline of nearly 900 other affordable units that are in various stages of planning and development. With more than 4,000 units under its ownership and management, the First Street project in Sarasota would tip their construction pipeline over 1,000 units — a 25% increase to the firm’s portfolio, which has traditionally grown through acquisitions and not new construction.

Real estate experts said delivering that number of affordable units would challenge even the largest national real estate firms, raising questions about whether Vengroff’s company has the capability — or the financial structure — to pull it off.

Dougherty, the Pinellas County developer, reviewed the proposal and pointed to what he called unrealistic per-unit construction costs, unusually low estimates for retail space and insurance and a developer cash contribution far below industry norms.

He also questioned the building design itself, noting that the 10-story tower would be classified as a high-rise, triggering stricter fire safety requirements that typically push costs higher. Other concerns include a deal structure that asks the city to contribute more than $15 million in land and parking for 75 units of affordable housing.

There’s also the company’s lack of experience with high-rise construction. One Stop Housing has never built a high-rise.

“The solicitation he submitted,” Dougherty said, “has a lot of fluff and is very light on actual details.”

The new proposal from Mark Vengroff shows a total capital investment of $31.6 million, with the city paying an additional $7.8 million of the first 10-story tower. | Image from Vengroff’s bid

Vengroff said his construction costs are lower than previous city plans because his firm would design, construct and manage the development, controlling all facets of the project.

“The purpose of this proposal is to offer the city of Sarasota a turnkey, mission-driven solution to one of the community’s most pressing challenges,” Vengroff wrote in his proposal to the city.

Should the first tower be successful, a second will then be built on the city’s other lot, with another 75 units, additional parking and ground-level retail.

The city would lease the land to Vengroff for free for 50 years, with Vengroff handling the leasing and the city owning the parking. The city would chip in another $7.8 million toward construction costs, records show.

“We’ve circled enough experts on downtown requirements for a tower like this,” Vengroff said “We feel very comfortable with our price point that we have shared with the city of Sarasota, and we have some hedge in the numbers.”

Kelly Kirschner is a former Sarasota city commissioner and mayor who contributes to Suncoast Searchlight. Email Kelly at hoyakelly@gmail.com. Derek Gilliam is an investigative/watchdog reporter for Suncoast Searchlight. Email Derek at derek@suncoastsearchlight.org