Sarasota, Bradenton developers score big tax breaks with “Rent-A-Cow” loophole

A state loophole is costing Sarasota and Manatee counties millions in lost revenue by allowing developers to tap a decades-old law meant to preserve agriculture and shrink the taxes on pastures they intend to pave over.

Known as Greenbelt, the law was designed to protect Florida farmland with rock-bottom tax rates but has been mastered instead by entities eyeing land for subdivisions and shopping centers. By leasing their land to cattle grazers and claiming it as agriculture until they’re ready to build, developers avoid the higher property taxes that come with new construction.

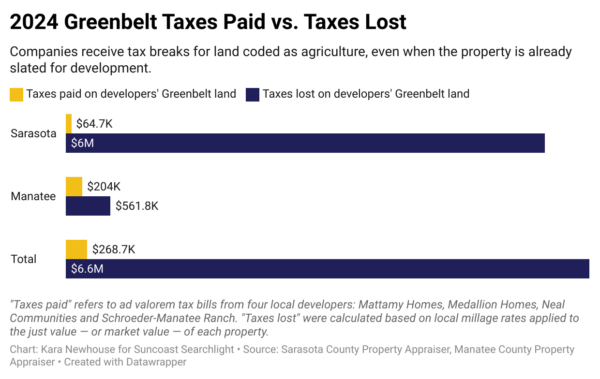

Some of the region’s most active builders and developers used the loophole to deprive Sarasota and Manatee counties of at least $6.6 million in tax revenue last year alone, a Suncoast Searchlight investigation found.

Officials are then left scrambling to find money for infrastructure to accommodate the growth – a burden that falls on the general tax base instead of the very companies profiting from the developments.

“We know they are playing the system,” said Manatee County Property Appraiser Charles Hackney. “But they are acting within the bounds of the law.”

“We know they are playing the system,” said Manatee County Property Appraiser Charles Hackney. “But they are acting within the bounds of the law.”

Using officer names and business addresses, Suncoast Searchlight identified more than 1,000 limited liability companies tied to the region’s most well-known local developers: Benderson Development Co., Schroeder-Manatee Ranch Inc., Neal Communities and Medallion Home; along with Canada-based Mattamy Homes, the developer behind the West Villages.

Reporters then matched those LLCs with the listed owners on the property rolls in Sarasota and Manatee counties to decipher how much land these developers control and how often they use the tactic. Suncoast Searchlight also combed through hundreds of pages of real estate deeds, property assessment records and tax bills to pinpoint the biggest beneficiaries. (Read more about our data analysis.)

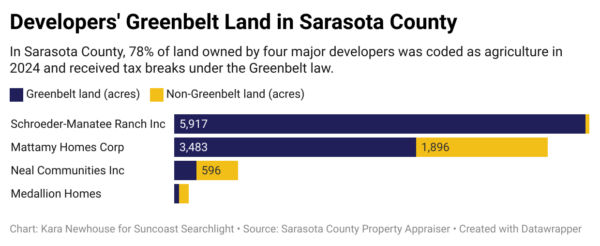

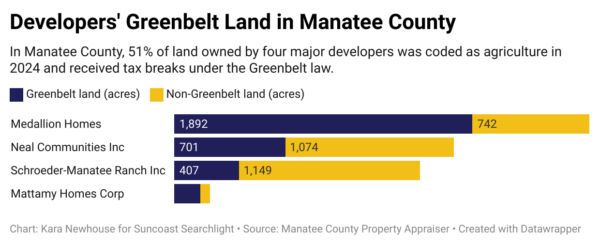

The investigation found that all but Benderson Development Co. had active Greenbelt sites during the most recent tax year. Together, the other four builders own at least 20 square miles – larger than the entire city of Sarasota – across the two counties that are coded as agriculture.

By claiming Greenbelt, developers erased almost 97% of the taxable value on properties worth more than half a billion dollars across Sarasota and Manatee counties, Suncoast Searchlight found.

Altogether, the four companies paid about $269,000 in ad valorem taxes last year on their Greenbelt sites.

Neal Communities paid $55 in ad valorem property taxes last year on a 6.4-acre commercial development site south of University Parkway that it bought nearly two years ago for $2.2 million.

Schroeder-Manatee Ranch paid $9 in ad valorem taxes last year on 6 acres in Lakewood Ranch with a market value of $1.9 million.

A company tied to Medallion Home used the loophole to pay $442 in property taxes for 59 acres of the former Foxfire golf course off Proctor Road already zoned for new residential development. For comparison, the owner of a 1,900-square-foot house in unincorporated Sarasota paid six times more.

“We have a rancher that leases the property and keeps cows there,” Medallion Home founder Carlos Beruff said in a text message. “Has for years.”

Ad valorem property taxes are the primary revenue source for local governments across Florida, which rely on the funds for roads, schools and police. The annual rates are set by elected officials, then assessed on the parcel’s determined value.

Sarasota County Commissioner Tom Knight | Courtesy photo

“This has been going on a long time,” Sarasota County Commissioner Tom Knight said. “It’s an antiquated law meant to help farmers of the era that’s not living up to true intentions. Developers are using it to save millions of tax dollars and not pay their fair share.”

Developers note that they are within the bounds of the law. Because their projects are not completed, they contend the properties add no strain to local governments, and therefore, they should pay agricultural rates.

Some builders said forcing them into higher taxes during the waiting and planning stages would prompt them to advance development sooner than intended, expediting the inevitable growth.

“If you have a piece of property that you’re allowed to do this on, then it’s not illegal,” Suncoast Builders Association CEO Jon Mast said. “These homes will bring way more property taxes.”

While not a tax exemption, the Greenbelt classification is just one of the many tax breaks given to property owners, including the $50,000 homestead discounts for year-round residents.

But as local governments seek to pay for the billions of dollars worth of infrastructure needs associated with population growth and new development, the cattle grazing loophole is exacerbating the shortfall.

“We’re growing houses now instead of crops,” Hackney said. “The larger developers in the area already have a relationship with people in the cattle business, so they’re ready.”

Decades later, Greenbelt fails to preserve agriculture

Between the postcard shores, inland Florida was long marked by miles of orange groves, roadside fields sprouting bright red tomatoes and strawberries, and cowboys pushing cattle through muddy prairies of mossy oaks and palm fronds.

That old farmland has disappeared to make way for suburbia.

To stop the sprawl, Florida lawmakers in 1959 adopted what is known as the Greenbelt law to protect farmers and preserve the state from over-development by offering steep property tax discounts on agricultural land.

All property before then was taxed on the value of its most profitable potential use, which often meant new development. That left a crushing tax blow to Florida ranchers, who as a result, were selling much of their land to eager builders with their eyes set on shopping malls and subdivisions.

“Would you rather make $1 million a year running an orange grove or sell the land to a developer for $30 million up front?” said Steve Geller, a Broward County commissioner, former Florida senator and practicing land-use attorney.

The Greenbelt law instead assesses taxes based on a property’s current use to reflect less-profitable industries like agriculture. The idea was to keep farmers and ranchers in business by saving them thousands of dollars each year.

Property owners must apply for the Greenbelt tax rate, with county appraisers evaluating applicants on the specific type of operation and income produced. If the appraisers determine the land meets the definition of a “good faith commercial agricultural use,” the lucrative tax break is awarded.

The classification applies to all commercial agricultural operations – like dairy, citrus groves or sod farms – but developers often turn to cattle grazing because it’s easier than running a full-fledged farm.

Critics of the loophole point to Walt Disney as among the first to take advantage of it decades ago when developing its tourist mecca of resorts and theme parks near Orlando. In 2006, the Associated Press reported Disney leased out almost 650 acres to a farmer to claim agriculture.

For decades, builders across the Sunshine State have turned to cattle grazers to save on tax bills at the expense of local governments.

While serving in the Legislature, Geller, a Democrat, coined a nickname for the loophole: “Hertz Rent-A-Cow.”

Cows graze on land in south Sarasota County that’s slated for development by Neal Communities. | Photo by Lily Fox for Suncoast Searchlight

He said the problem is the state left open the legal interpretations of what are considered “bona fide” agricultural uses, allowing real estate developers and their attorneys to pick apart the broad language.

“All you have to show is that you’ve got six chickens, a pig and horse,” Geller said, tongue-in-cheek. “And that’s ridiculous.”

In the early 2000s, Geller introduced a statewide overhaul to curb the rampant misuse of Greenbelt, including clawbacks modelled at the time after a Texas law allowing local governments to recoup taxes if a rancher decided to build homes.

Although Geller chaired the Senate’s Committee on Agriculture and Consumer Services, his measure died with little support. There have been sporadic attempts by others to close the loophole since, but nothing has gained traction.

It’s gone on for so long, builders have become brazen. Tampa Bay Times archives from 1990 cite an example at the time when a developer planned to build an industrial complex on 529 acres near Interstate 75 in Hernando County worth $1.8 million.

The company’s property taxes were $260 lower than a nearby three-bedroom home, the newspaper had reported.

Area attorneys, elected officials and growth-control advocates contacted by Suncoast Searchlight were stunned to learn the extent to which the loophole has been exploited.

“Is it really an agricultural use to have two or three cows on your 500-acre property?” quipped Dan Lobeck, a Sarasota attorney who heads the advocacy group Control Growth Now. “It does give offense to a reasonable person.”

In Sarasota County, the number of agricultural properties has shrunk from more than 900 in 2016 down to about 600 last year, according to the property appraiser. There are just 21,053 acres of actual vacant land left in the county, not counting parks and other rights of way.

Manatee County has 70,504 acres of vacant land.

The loss of agriculture comes as demand for local food and produce has never been higher. Florida cattle and farm trade groups did not return requests for comment.

“It’s not just the direct loss of farmland – even the farmers still here are in danger of development,” said Anne Miller, acting executive director with Community Harvest SRQ, which goes into farms to pick leftover produce to reduce waste.

Ranchers ward off new development

Hugh Taylor learned his trade through decades saddling a horse before sunrise to move herds across his ranch along the river just south of Myakka City.

Homebuilder Pat Neal studied business in Ivy-league classrooms at University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Finance, gaining his influence in the Florida Legislature in the 1970s and 80s.

While Neal is expanding his homebuilding empire – his companies have built more than 20,000 homes in Florida – Taylor is focused on how his ranch can survive getting sandwiched by a new home development and a golf course.

“We have seen more and more homes go up,” Taylor said. “It does concern us. It has definitely changed the area.”

He’s unsure of the long-term effect on his cattle.

“Your property is your land, so you can do with it whatever you want,” Taylor said. “As long as it doesn’t interfere with me.”

Cows peer over the fence of a property for sale in Lakewood Ranch. | Photo by Lily Fox for Suncoast Searchlight

Greenbelt was crafted decades ago to help ranchers like Taylor. Yet it is builders like Neal who have mastered the law’s loophole.

Two years ago, a company controlled by Neal Communities called Sioux Investment Partners LLC purchased two tracts of land totaling 317 acres east of Interstate 75 for $46.8 million.

The parcels are zoned for planned development – and Neal has filed to build more than 6,500 homes, 250,000 square feet of commercial space, and 120,000 square feet of offices on the site and nearby land over the next two decades through a project known as 3H Ranch.

A traffic study by consultant Stantec on 3H Ranch predicts thousands of new car trips during peak commute times, increasing loads on Clark, Beneva, and Proctor roads, along with Honore Avenue.

While Neal Communities waits for construction, the company tapped Greenbelt. Despite the clear value of the sites, by using the property for grazing, Neal carved the taxable value from $36.8 million down to $131,500.

Last year, Neal paid $1,509 in combined ad valorem property taxes on both properties.

That’s less than half of the tax bill for an average middle-class home in Sarasota County.

In an emailed statement, Pat Neal said the properties in question are used for agriculture, so they were entitled to the breaks.

“The purpose is to allow practitioners of agriculture to stay in agriculture and not be taxed out of business,” Neal wrote in the statement.

“The properties that you have referenced are used as agricultural property,” he added. “They are entitled by law and court law to be classified as they are…as agriculture.”

Greenbelt is used across the Suncoast, from the pastures of Parrish to the marshes of West Villages in North Port – and it’s not just local developers.

National builder Pulte Home Co. snapped up 112 acres in Englewood two years ago for $13.1 million. The company, which last year generated nearly $18 billion in revenues, paid just $531 in ad valorem property taxes for the planned development site in 2024.

A subsidiary of Canadian builder Mattamy Homes paid Sarasota County $106 in ad valorem taxes last year on a 52-acre parcel worth $3 million in the massive West Villages development near North Port.

For comparison, the owners of a 1,992-square-foot house built 30 years ago on Pinehurst Street in Sarasota paid $3,694. The home is worth $337,200.

Mattamy representatives did not respond to requests for comment.

Developer expands Lakewood Ranch with steep tax discounts

John Schroeder first began cobbling together properties now known as Lakewood Ranch in 1905 for lumber and resin. The land was used for agriculture and hunting through the 1960s, then citrus and cattle in the 1970s and 80s.

In the 1970s, the Sarasota-Bradenton Airport Authority proposed building a new airport at Lakewood Ranch, and local officials also pitched ideas for a sewer facility and trash dump there. Schroeder-Manatee Ranch – now one of the region’s largest real estate developers – instead spun the land into a massive residential and commercial development rivaling The Villages retirement community near Ocala.

With shopping and business hubs, Lakewood Ranch encompasses more than 30,000 acres hugging Manatee and Sarasota counties and an estimated population of 72,000 people. That includes at least 15,000 new residents since 2020 alone.

From its early roots in agriculture to its new communities under development, Schroeder-Manatee Ranch has taken the Greenbelt law full-circle.

SMR owns the most land of any of the major developers in Sarasota County, with at least 5,974 acres. Of that, 99% of the land is classified as agricultural, according to the Suncoast Searchlight analysis.

Despite intentions to develop, SMR gained Greenbelt classifications that chopped the taxable value of its agricultural property across the two counties from $302.5 million to just $3.9 million, records show. That shrunk the ad valorem taxes last year to about $53,000, according to a Suncoast Searchlight review of tax bills.

Public relations representatives at SMR did not respond to calls and emails seeking comment.

Growth control advocates point to SMR’s influence as the reason Sarasota and Manatee counties have moved the urban boundary lines – designed as the border between primary development and agriculture – farther east, gutting any semblance of old Florida’s country lifestyle.

It’s the aggressive ebbing away of agricultural land that Greenbelt was supposed to stop.

“What they’re trying to do now is get rid of the rural,” said Michael Hutchinson, a board member with the grassroots nonprofit Keep the Country Country. He lives in a 1,700-square-foot home on about 5 acres and remembers when everything east of I-75 was considered rural.

“It’s getting ridiculous,” he said. “It’s a different way of life, but people have sort of given up. They see the writing on the wall.”

Michael Hutchinson, a board member with the grassroots nonprofit Keep the Country Country, at his home in rural Sarasota County. | Photo by C. Todd Sherman for Suncoast Searchlight

SMR uses the designation on at least 31 parcels in Sarasota and another six in Manatee. For example:

- On 619 acres in Sarasota County central to the Lakewood Ranch expansion, a subsidiary of SMR paid $1,197 in property taxes last year. The site was valued by the county at $18.1 million.

- For another 200 acres near University Parkway, SMR paid $791 in taxes on a property with a market value of $5.3 million. The tax bill was $22 for a similar 32 acres tied to the expansion.

“The real agriculture for the future of Sarasota County is in doubt,” said Glenn Compton, chairman of the environmental nonprofit ManaSota-88 Inc. “It’s under constant threat of development going next door.”

Llamas, homes or farms? Land owners denied tax breaks put up fight

During the past two decades, thousands of land owners have petitioned the Manatee and Sarasota property appraisers for agricultural tax classifications under Greenbelt.

Many are operating more traditional agricultural businesses, like Dakin Dairy, Detwiler Farms and Jones Potato Farm. Others are builders, real estate holding groups or acquisition companies.

Not everyone who applies gets the break. An applicant must show the operation is at least attempting to become profitable. That means the builders who qualify are not only saving on taxes but oftentimes earning revenue from third-party cattle grazers who rent the land.

Property appraisers say their hands are tied. Like it or not, they are obligated to follow the state law and insist that they scrutinize every application. Just because an applicant is a known developer by trade does not mean they cannot qualify.

When developers buy a property coded under Greenbelt, they keep the classification until the following January. Even if they start building right away, owners can reduce the property’s acreage set aside for agriculture while developing the rest – allowing them to benefit from tax breaks while construction is already underway, Sarasota County Property Appraiser Bill Furst said.

“The more you look into the law and guidelines, the more vague it is,” Furst said. “There’s not much of a scorecard. There’s no A, B or C.”

Furst cited examples during the Great Recession when builders who completed roads, sidewalks and street lights for an intended new subdivision – but ran out of capital – just fenced up where the homes were to go, put in some cows and called it agriculture.

He said the loose guidelines make it almost impossible for his office to win a case challenging the classifications.

Last year, the Sarasota County Property Appraiser rejected 74 applications, at least in part, from property owners seeking the discount. Among those shot down were companies tied to SMR, Neal and Beruff, records show.

The property appraiser cannot dismiss a site based on size, but in Sarasota, Furst asks it be at least 10 acres. His office looks for things like fencing – land owners whose property was not even closed off have tried to apply – and uses aerial imagery to confirm cow counts.

From last year’s denials, petitions by builders like West River Village Development and Deluxeton Homes are still fighting in hearings scheduled through April.

In Manatee County, the property appraiser said his office spent months arguing with a property’s owners who tried to say their pet llamas qualified.

Elected officials say addressing the loophole is just one step in a range of controls needed to regulate overgrowth.

“We need to hold developers accountable,” Manatee County Commissioner Tal Siddique said. “Agriculture is an important part of our history and heritage.”

Josh Salman is a deputy editor/senior investigative reporter and Kara Newhouse is an investigative data reporter for Suncoast Searchlight, a nonprofit newsroom of the Community News Collaborative serving Sarasota, Manatee, and DeSoto counties. Learn more at suncoastsearchlight.org.