Sarasota Ballet dancers leave in droves, citing toxic culture and instability

Over the past two decades, The Sarasota Ballet has transformed from a little-known regional troupe to an internationally acclaimed draw, thanks to the vision, connections and drive of Director Iain Webb and his wife, Assistant Director Margaret Barbieri, who have made the ballets of British choreographer Sir Frederick Ashton the company’s signature.

But that winning formula appears to be faltering.

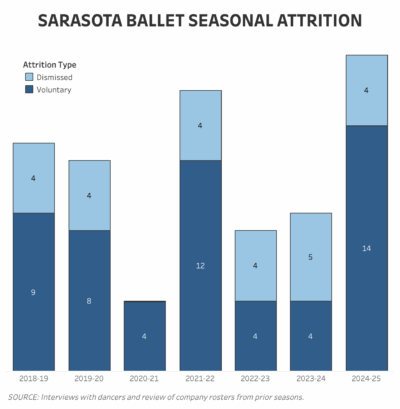

Nearly half the company’s dancers — including its top two female principals — are leaving after a season marked by strained relationships with leadership, internal strife and what the dancers describe as a toxic work culture.

The exodus can’t be attributed simply to attrition, a labor dispute or artistic sensibilities. Instead, it presages a reckoning between legacy and evolution, artistic control and dancer autonomy, reverence for tradition and a need for change.

Interviews with 13 of 18 departing dancers detail an environment of fear, favoritism and frustration they claim is perpetuated by the very leadership that helped raise the company’s profile. Though all declined to have their names published — citing “career suicide” — their statements were corroborative and in line with sentiments expressed by a former Sarasota Ballet dancer who was willing to go on the record.

Among the dancers’ primary complaints: Tempestuous outbursts and harsh verbal attacks by the director, often in front of colleagues; mercurial and punitive casting decisions based on factors other than artistic ability, work ethic or suitability; inadequate performance preparation due to a failure to delegate responsibilities; and the squelching of individual artistic expression.

Among the dancers’ primary complaints: Tempestuous outbursts and harsh verbal attacks by the director, often in front of colleagues; mercurial and punitive casting decisions based on factors other than artistic ability, work ethic or suitability; inadequate performance preparation due to a failure to delegate responsibilities; and the squelching of individual artistic expression.

It’s a level of dysfunction that Josh Fisk, who danced with The Sarasota Ballet from 2022-2024, said he fully acknowledged only after spending last season with the Cincinnati Ballet. There, he said, he not only enjoys better pay, shorter hours and a new purpose-built facility, but an “open door” policy between dancers, staff and leadership.

“This year opened up my eyes to things that happen in Sarasota that would have got you fired or shunned that don’t happen in Cincinnati,” he said. “There’s a higher level of respect from the artistic staff. In Sarasota, it was a blame game. Here we have monthly meetings with staff and dancers where everyone is straightforward about what they feel.

“In Sarasota a meeting ‘upstairs’ was never a good thing. My director now is super receptive and happy to talk about concerns, anytime. We all — the dancers, the staff, the administration — work together to produce the best possible result.”

Get stories like this delivered to your inbox weekly: Sign up for the Suncoast Searchlight newsletter

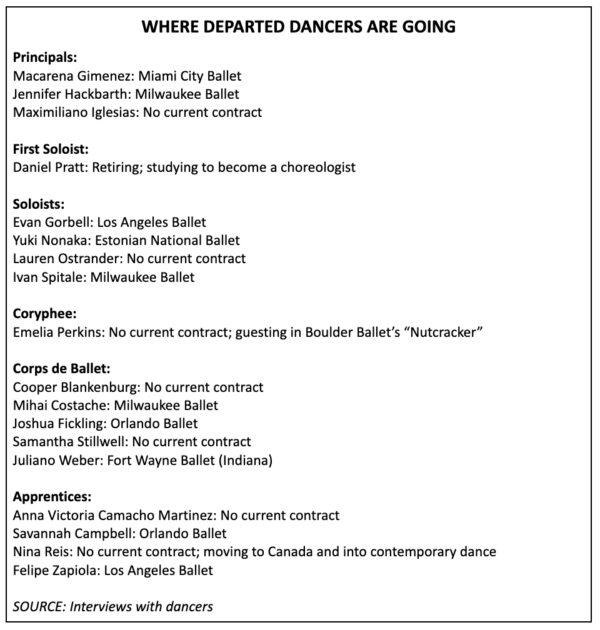

The mass exodus has put The Sarasota Ballet in a precarious position. In addition to the two exiting principal ballerinas — Macarena Gimenez and Jennifer Hackbarth — five of the company’s seven soloists are gone. This comes as the company heads toward a mid-July engagement at the prestigious Jacob’s Pillow dance festival in Massachusetts, where it is scheduled to present an ambitious triple bill that includes Ashton’s “Birthday Offering,” with seven demanding female soloist roles.

Macarena Gimenez and her husband, Maximiliano Iglesias, in a promotional image from “Romeo and Juliet.” | Photo by Frank Atura for Sarasota Ballet

The company declined to say if it has hired any new dancers, but its website states it is “looking for Principal and Soloist dancers to join our critically acclaimed company for the 2025-2026 season.” In a press release issued last week it announced Misa Kuranaga, a principal with the San Francisco Ballet who has guested with the troupe previously, will appear in the performance at Jacob’s Pillow as a “resident guest principal,” as well as in three other programs during the upcoming Sarasota season.

The departures have come with consequences for the dancers, too. Among them, only Gimenez is going to a more prestigious company, the Miami City Ballet. Her husband, Maximiliano Iglesias, a Sarasota principal, was not offered a position there and declined a contract renewal in Sarasota, leaving him unemployed. Others either are going to lesser companies or have no job prospects at all.

Webb and Executive Director Joseph Volpe declined to answer questions, saying in a statement that it “would be inappropriate and unprofessional to discuss our dancers’ abilities, attributes or frailties publicly.”

As of publication, the president of the ballet’s board of directors, Sandra DeFeo, had also not responded to multiple requests for comment.

In the past, both Webb and Barbieri have professed — to donors, audiences and reporters — that the long hours they devote to their jobs, their commitment to ambitious programming and their efforts to elevate the company’s profile have all been for the sake of the dancers.

The dancers, both have said, are their “top priority” and that restaging the historic Ashton ballets is a labor of love they undertake to pass on the legacy to younger generations.

And across the board, dancers still profess respect for Webb and Barbieri’s own careers with the Sadler’s Wells Royal Ballet, for their depth of historical knowledge, and for the attention the company has received. This is not a personal attack or vendetta, they insist; it is a plea for mutual professional respect.

“Even if I cried every day for two years, I don’t hate them,” said a dancer who recalled being happier in earlier days with the company. “I hate the way I was treated.”

To be sure, ballet companies are notoriously places of drama and tumult. The existing stereotypes, from the autocratic director to the back-stabbing prima ballerina, have become the stuff of today’s movie and television shows. Dancers, like most artists, can be dramatic, emotional and overly sensitive.

But in this case, the dancers said, the breakdown in relations and communications was not amongst themselves, but between artistic management and dancers and that it created a culture of unpredictability, hostility and retaliation.

Private turmoil replaced praise behind Sarasota Ballet’s public success

The escalating tensions erupted in early January when soloist Lauren Ostrander, who had been with the company for seven seasons, resigned precipitously (as confirmed by the company) with only a note of thanks to the directors. Though the abrupt departure initially caught her colleagues by surprise, many later told Suncoast Searchlight they immediately understood why she was going even without explanation.

About the same time, principal Jennifer Hackbarth, who had been through a divorce and a difficult time in her personal life, resigned after her request to be excused from a program was denied, an incident corroborated by multiple sources.

Jennifer Hackbarth and Ricardo Rhodes in a promotional image. | Photo by Frank Atura for the Sarasota Ballet

Neither of these departures was acknowledged publicly to audiences or donors, despite both dancers’ high visibility and popularity. Neither Ostrander nor Hackbarth were willing to comment for this story.

By the time ballet companies are hosting annual auditions for next season’s contracts in February, one former Sarasota Ballet dancer said, most of his colleagues were seeking jobs elsewhere. Many of those auditioning later told Suncoast Searchlight they hid their auditions from management, fearing retaliation, lost or lesser roles and jeopardized contract renewals — concerns fueled by past instances where even personal choices or friendships outside the studio appeared to influence casting decisions.

While it’s fairly common for corps members — the lowest rank of dancers who primarily perform in groups and crowd scenes — to audition elsewhere for more stage opportunities, even higher-level soloists were auditioning.

At The Sarasota Ballet, the ascending ranks include apprentices, who are not full company members, corps, coryphee, soloists and principals.

Until this year’s contract negotiations — which resulted in 5-15% salary hikes across the ranks — Sarasota Ballet dancers were among the lowest paid in the industry, with a corps dancer making $724 a week. That’s less than the “living wage” in Sarasota of $907.

A six-day-a-week work schedule and just four days of PTO per season also contributed to low morale, the dancers said. But they insisted these concerns were secondary to their primary complaint: an environment of constant instability, where the ground always seemed to shift beneath them.

One month they said they might be the director’s favorite and the next, frozen out, or “blacklisted,” as the dancers came to call it amongst themselves. Keeping company members guessing, insecure and questioning their own abilities and value seemed to be a “mental game” the director enjoyed, said a recently departed dancer who had spent five years with the company.

“Suddenly, the things they loved about you are your bad things,” said another former multi-year company member. “Suddenly it shifts, everything is wrong. And because it’s so drastic and there’s not a series of events that allows dancers to feel it’s logical, you start to question everything. What did I do? Their actions and their words don’t match and it leaves you in a spiral.”

Sarasota Ballet leadership accused of stifling dancers and controlling artistry

As a result of the allegedly quixotic decision-making, dancers said daily interactions between them and Webb and Barbieri — whether in rehearsals or just crossing paths in the hallways of the Asolo Theatre, where the ballet is based — became increasingly strained and uncomfortable.

Sometimes there were harsh critiques or inappropriate remarks in front of colleagues, fueling the atmosphere of fear, distrust and intimidation, the dancers said.

Not only were personal interactions fraught, but frustrations mounted during rehearsals when Barbieri — who stages most of the historical Ashton ballets she once danced in herself — refused to share responsibilities, even with the ballet master and ballet mistress, whose jobs are intended to spread the workload and facilitate coaching.

Dancers said that, at 78, and without the ability to physically demonstrate choreography any longer, Barbieri’s gifts would be better put to use now as a “finisher,” putting a polish on the details of a ballet before a performance. They said they often felt inadequately prepared for roles she staged and resorted to watching videos of other performers to learn the choreography.

Dancers said that, at 78, and without the ability to physically demonstrate choreography any longer, Barbieri’s gifts would be better put to use now as a “finisher,” putting a polish on the details of a ballet before a performance. They said they often felt inadequately prepared for roles she staged and resorted to watching videos of other performers to learn the choreography.

“The company got the rep it has for dancing Ashton’s ballets in the way they used to be danced,” acknowledged a veteran dancer, “but because management sees Maggie as the key to that, everything has to go through her or it would dilute the product or reflect badly on her. That creates inefficiencies, so something that should have been a positive became a negative.”

Because Barbieri is seen as the keeper of the Ashton legacy, which she and Webb revere, “everything has to go through Maggie,” said one dancer. Any hint of questioning or suggestion of nuance was sharply rebuked.

That level of control also left the higher-ranked dancers frustrated artistically, because they said they could not bring their own sensibilities to a performance. Keeping the choreography of a historical ballet accurate is important, they acknowledged, but turning it into a “fossil” or “museum piece” by squelching the greater technical abilities of today’s dancers does not allow the art form to grow.

“I never felt comfortable to interpret a role differently, I had to do a role exactly as dictated by [Barbieri],” said a female dancer. “If you do something differently, if you give even a little bit of interpretation to a character — unless she thinks it’s ‘charming’ — she’ll yell at you for disgracing Ashton’s name.”

Suncoast Searchlight shared the specific allegations with the company, but it did not comment on them or make Barbieri available for an interview.

In a place like Sarasota, where the ballet is well-supported by wealthy donors and performances are received by audiences that, without fail, jump to their feet for standing ovations at a program’s end, such a stressful working environment is a paradox, said a departing corps member.

“There’s no need to make it so stressful to the point where dancers are breaking down and going home feeling shit about themselves,” he said. “I can honestly say every dancer, at some point, has gone home feeling absolutely dreadful.”

In choosing to publicly share their concerns, the dancers said they hope The Sarasota Ballet can again become the “dream” workplace they thought it was when they accepted contracts here.

Webb and Barbieri “have achieved an incredible thing,” acknowledged a longtime company member. “They took a company no one had heard of and gave it international acclaim, which is no mean feat. But the company has changed and they haven’t. I would love to see a development in their artistic vision.”

Carrie Seidman has covered the arts and, in particular, the ballet, in Sarasota for more than a decade. She is a contributing writer for Suncoast Searchlight, a nonprofit newsroom of the Community News Collaborative serving Sarasota, Manatee, and DeSoto counties. Learn more at suncoastsearchlight.org.