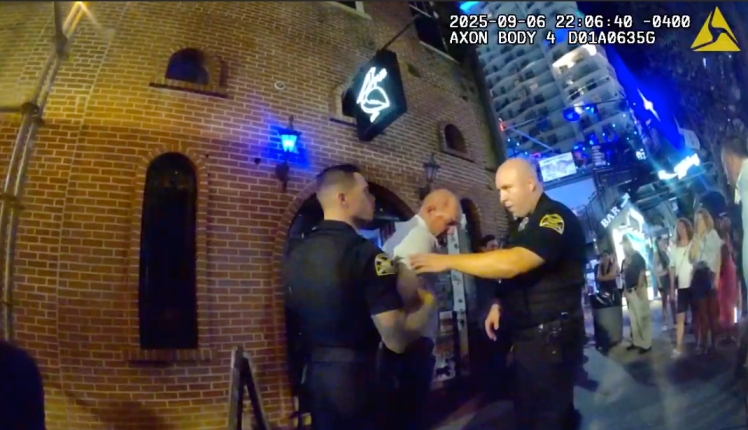

Manatee County Sheriff's Lt. Randall Crawford (left) being questioned by a St. Petersburg police officer outside a nightclub on Sept. 6. | Image from St. Petersburg Police body camera video

Manatee County Sheriff’s Office accused of double standard after September scuffle

As crowds looked on from a line waiting outside the Good Night John Boy nightclub in downtown St. Petersburg, bouncers of the bar had a man with a bloody face pinned to the concrete.

The man had tried to cut in front of others to get back into the 1970s-themed club, known for a large disco ball that hangs above the dancefloor. When confronted by a bouncer, the man head-butted him.

This was no ordinary unruly patron that night in early September. It was 39-year-old Randall Crawford — a lieutenant with the Manatee County Sheriff’s Office — who was out partying with other command-level deputies from the agency.

St. Petersburg police did not know this when they arrived and handcuffed Crawford, shooing away his colleagues as they tried to intervene, according to body camera footage from the incident. Police said they had enough evidence to arrest Crawford for head-butting the doorman, even telling the bouncer, “I’m assuming — I know he’ll go to jail.”

But shortly after Crawford identified himself as a fellow law-enforcement officer, police turned off their body cameras, uncuffed Crawford and — after the bouncer declined to press charges — dropped the investigation. The Manatee County Sheriff’s Office’s internal affairs probe cleared Crawford of wrongdoing and imposed no discipline on him.

Manatee County Sheriff’s Lt. Randall Crawford (middle) being detained by St. Petersburg police officers outside a nightclub on Sept. 6. | Image from St. Petersburg Police body camera video

The only person punished in the affair was Crawford’s colleague, Maj. Thomas Porter, who received an 86-hour suspension for giving police at the scene a false name. That suspension took effect in early November and only after reporters requested the internal affairs reports.

The incident and its aftermath provide a rare glimpse into how high-level members of law enforcement are treated during external and internal police probes and raise questions about whether they’re held to the same standards as everyone else, according to an investigation by Suncoast Searchlight and the Bradenton Herald.

Experts told the media organizations that the situation on the Suncoast is illustrative of a problem that has plagued law enforcement agencies nationwide. Other departments have overcome it, the experts said, by adopting policies that define punishments more clearly and reserve the most severe discipline for agency leaders, as they should know the rules the best.

“Police aren’t holding themselves to the same standards that they would hold members of the public to,” said Lauren Bonds, executive director of the National Police Accountability Project. “I think that is never good for trust and belief in any law enforcement agency.”

As part of the media organizations’ investigation, reporters reviewed body camera videos from the scene, examined police reports from St. Petersburg and internal affairs documents from Manatee County, spoke with officials at both agencies, as well as with former Manatee County Sheriff’s Office deputies. They also interviewed national police accountability experts about both agencies’ handling of the incident.

Among the media organizations’ findings:

- St. Petersburg police identified the bouncer as the victim and Crawford as the suspect, a conclusion supported in the police reports by witness statements and nightclub security footage. But when Manatee County reviewed the same evidence, its internal affairs report cast the lieutenant as the victim. Neither agency would release the nightclub security footage to reporters, citing an exemption from public records laws.

- Manatee County sheriff’s deputies were uncooperative and untruthful with St. Petersburg police at numerous points during the event, according to records and body cam footage. Crawford told police “he did not know” any of his friends’ names that night, and Porter identified himself to officers using a name that was not his own. At least one high-ranking Manatee deputy on the scene attempted to intervene in the investigation and was repeatedly told to stand back.

- The timeline of the Manatee County Sheriff’s Office review raises questions about how the agency handled the case. While records show internal investigators reviewed body cam footage days after the Sept. 6 incident, there is no evidence of them interviewing anyone until a month later.

- The internal affairs’ conclusion has created division within the agency. Former deputies who spoke to Suncoast Searchlight pointed to more than half a dozen cases where street-level employees faced more severe punishment for what they characterized as less serious issues. A deputy in one case was suspended four days for taking spent shell casings from the sheriff’s office firing range. Another resigned for detonating a flashbang grenade at a party where no one was injured.

Crawford and Porter were not the only ones there that night from the Manatee Sheriff’s leadership team.

Body camera footage showed Col. Patrick Cassella — the agency’s second in command only behind Sheriff Rick Wells — watching as his coworker was in handcuffs. A police officer repeatedly warned Cassella to move back.

“Twenty-five feet, or you’re going to jail. Twenty-five feet. It’s not that hard,” the officer told Cassella, according to the footage.

Col. Patrick Cassella of the Manatee County Sheriff’s Office was repeatedly told to stand by St. Petersburg police during the Sept. 6 incident. | Image from St. Petersburg Police body camera video

To be sure, no one was seriously injured during the September scuffle, and the Good Night John Boy doorman declined to press charges. St. Petersburg police told reporters they typically defer to victims in simple battery cases and don’t make arrests when victims decline to prosecute, except in domestic violence situations.

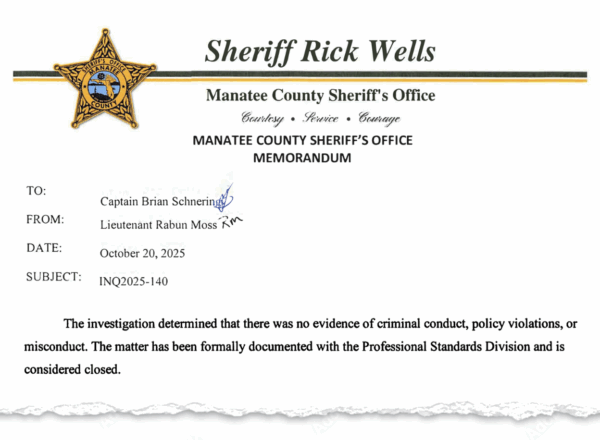

Manatee County Sheriff’s Office spokesman Randy Warren said the agency’s investigators found “no evidence of criminal conduct, policy violations or misconduct involving” Crawford, and the sheriff’s office suspended Porter without pay for “conduct unbecoming.”

One witness to the fight, who based on body camera footage appears to be Palmetto City Commissioner Scott Whitaker, told police that the bouncer was the aggressor. The man in the video was out that night with the deputies. His comments were not included by St. Petersburg officers in the narrative of what happened that night. Whitaker did not respond to an email and phone calls from a reporter.

“Our friend, he didn’t, he wasn’t making an aggressive move,” the man who appears to be Whitaker could be heard telling police on the body camera footage. “He was defending himself.”

Yolanda Fernandez, a St. Petersburg police spokesperson, said that officers followed policy when they turned off their body cameras as the suspect was in custody and the situation had calmed.

“There was no investigative value to continue recording,” she said.

Still, after reviewing the nightclub’s security footage, St. Petersburg police gathered enough probable cause evidence to jail Crawford and charge him with misdemeanor simple battery had the bouncer wished to press charges, according to a St. Petersburg police report obtained in a public records request.

Reporters shared the documents obtained from the incident and the internal affairs investigation with experts who specialize in police misconduct. After examining them, the experts expressed serious concern about the culture within the Manatee County Sheriff’s Office and the agency’s response to the incident.

Bonds, a civil rights attorney and the executive director of the National Police Accountability Project, said both the fight and untruthful statements provided to St. Petersburg police by command-level deputies undermine public trust and should raise red flags.

“We don’t want police officers to be above the law,” Bonds said. “That’s something that just about everybody can agree about.”

More from Suncoast Searchlight: Sign up for the weekly newsletter

Dueling reports paint different pictures

The St. Petersburg police reports and the Manatee County Sheriff’s Office internal affairs investigations reviewed the exact same evidence of the incident.

Both came away with different conclusions.

According to body-cam recorded interviews with Crawford and the bouncer, the incident began inside the club when an unidentified man allegedly shoved Crawford’s wife, prompting Crawford to “go after him.” Crawford followed either the man or his wife — or possibly both — outside of the club, although it was unclear from his statements which one.

One of the narratives from the St. Petersburg Police report about the Sept. 6 incident. | Suncoast Searchlight illustration based off the actual document

When Crawford tried to re-enter the club, the bouncer told police he cut in front of a line of would-be patrons but was stopped by security. Crawford then walked a short distance to the business’s VIP entrance and ducked under the rope.

While instructing Crawford to the back of the line, the bouncer shoved Crawford. Crawford responded by head-butting him. Several Good Night John Boy security members jumped to their coworker’s defense and pinned Crawford to the ground until police were flagged by the nightclub manager.

Crawford, who was slurring his words and bleeding from his face in the footage, repeatedly told police he was looking for his wife. He provided little description of the man who allegedly shoved her, except that he was white and had a full head of hair. Officers did not see his wife that night and did not get a statement from her; no other statements in the police report corroborate this part of his account.

Reporters left two voicemails and a text message seeking comment at a number linked to Crawford. Those messages were not returned.

The bouncer, which the news organizations are not naming because he is listed as a victim, did not return phone calls from reporters seeking comment. He told police his lip was swollen after Crawford smashed his head into his face. Reporters also reached out to Good Night John Boy by email; they did not get a response.

Manatee County’s investigation into Crawford’s behavior that night paints a different picture.

According to a memo written by Lt. Rabun Moss and based on a review of police reports, body camera footage and nightclub security footage — as well as an interview with Crawford — Crawford’s wife was “physically harassed” after the two became separated, and Crawford left the bar to search for his wife before trying to reenter.

The memo omits him cutting in front of other people waiting in line. Instead, it described Crawford as getting “forcefully pushed” by the bouncer — stating that “Crawford observed the staff member reaching toward him, prompting him to react defensively by attempting to head-butt the individual.”

Manatee County Sheriff’s Office provided no record of the conversation Crawford had with internal investigators.

Manatee County Sheriff’s Office cleared Lt. Randall Crawford of wrongdoing. | Suncoast Searchlight illustration based off Manatee County Sheriff’s Department Internal Affairs memo

The memo ended by clearing Crawford of any wrongdoing.

Christopher Mercado, a retired New York City Police Department lieutenant and professor at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice, said the decision not to discipline Crawford signals a leadership problem within the agency.

Mercado, who reviewed body camera footage at the request of reporters, called this a case of “white-shirt discipline” — coined for the white shirts worn by command-level officers in New York City. White-shirt discipline is characterized by high-ranking law enforcement officers avoiding discipline in circumstances that would see patrol-level cops punished.

“When you peel back the layers,” Mercado said, “it’s rules for different groups.”

A false name and withheld information

After the police arrived on scene, at least two Manatee County Sheriff’s Office’s top brass appeared evasive when responding to questions from officers working the case.

Porter, the major in charge of the sheriff’s office corrections bureau, misidentified himself as Billy Eurice when St. Petersburg police officer Tabitha Gerry asked for his name. He even spelled out the last name so she would get it right in her report, according to Gerry’s statements to Manatee County investigators.

A person with the same name was present with the deputies that night, according to a police report. Reporters left a message for a number associated with Eurice but he was not immediately available.

Gerry later realized the name was incorrect after running it through a police database and noticing the photo did not match the man she questioned. She correctly identified Porter only after reviewing the nightclub’s security footage and driver’s license scans of those who entered the establishment.

Manatee County Sheriff’s Maj. Thomas Porter was disciplined for misidentifying himself to St. Petersburg police during a Sept. 6 incident. | Photo courtesy of the Manatee County Sheriff’s Office

Gerry told Manatee County investigators that Porter said multiple times that he was a major at the sheriff’s office, although she also said that Porter was not attempting to use his position to influence the outcome of the St. Petersburg investigation.

Porter told internal investigators that he did not remember providing the false name to police or mentioning his rank.

“I don’t recall talking to her really at all,” he said, according to a transcript of the interview.

Florida law says anyone who knowingly provides false information to a law-enforcement officer about an alleged crime has committed an offense. A St. Petersburg police spokesperson said they did not investigate Porter misidentifying himself as a crime because he was not involved in the incident and it happened after police concluded their investigation into the scuffle.

When a reporter called a number associated with Porter, a man answered but hung up after the reporter identified himself.

It wasn’t the only time that evening that a deputy failed to give police complete or accurate information.

When St. Petersburg police interviewed Crawford a second time after he was transported to St. Anthony’s Hospital, he said he did not remember much of what had happened at the club nor names of the people in his party, according to body camera footage.

“Do you remember what happened with your wife?” St. Petersburg Officer Jonathan A. Reisz asked.

“Not much,” Crawford said.

Reisz then pressed Crawford on who he was with at the nightclub.

“You don’t know either one of their names?” Reisz asked.

“As far as you’re concerned, I don’t,” Crawford responded.

The Manatee County Sheriff’s Office described Crawford as cooperative with St. Petersburg police.

“By the time [Crawford] arrived at the hospital, the St. Petersburg Police investigation had already concluded, and he was not obligated to provide any further information about the incident,” Sheriff’s spokesman Warren said in a statement to Suncoast Searchlight and Bradenton Herald.

The sheriff’s office policy states that employees “shall be truthful and shall not knowingly make misleading, false, or untrue statements.”

When reporters asked the sheriff’s office why it did not investigate Crawford for appearing to have violated that same policy, Warren said Crawford “was polite and cooperative with the officers throughout the process.”

Manatee County Sheriff’s Lt. Randall Crawford at St. Anthony’s Hospital after a scuffle outside a St. Petersburg nightclub on Sept. 6. | Image from St. Petersburg Police body camera video

Experts expressed concern about how Crawford withheld information about what happened that night at the hospital and the false name provided by Porter.

“He’s not an amnesiac,” Mercado, the former NYPD lieutenant, said of Porter’s answers. “That’s a bunch of BS. There’s no reason why he’s playing games.”

Mercado said the response from law enforcement when their deputies make mistakes can be a barometer of a department’s culture.

“Transparent policing, especially in police discipline, is a foundational point in police-community trust,” Mercado said. “There are obvious cultural/behavioral and professional conduct questions for the command staff of that department.”

Drawn-out timelines raises questions

Questions also remain about the timeline of the sheriff’s office internal affairs investigation and why the case was not immediately made public by the agency.

Capt. Brian Schnering, the head of professional standards at the sheriff’s office, opened the investigation Sept. 7 — the day after the altercation at the nightclub. Yet it took more than a month before the first interview was recorded in the file, according to public records. Reporters asked the agency why it waited but did not get a response.

After Porter’s investigation concluded, the finding of “conduct unbecoming” was not included in the department’s list of closed internal affairs investigations that the sheriff’s office posted in an employee portal, according to sources with knowledge of that internal system.

Warren said that list was revised on Nov. 6 after the sheriff learned that Porter’s discipline had not been included in the log. The investigation into Crawford was closed on Oct. 20; Porter’s was closed on Oct. 21.

On Nov. 6, Porter began his 86-hour, unpaid suspension. That was just three days after reporters asked for the results of the internal affairs investigation.

When asked about the timeline of Porter’s suspension, Warren said that “for payroll purposes, all employee unpaid leave begins in the subsequent pay period. Supervisors also have the authority to schedule days off according to what is in the best interest of the agency.”

Perceived double standard creates division within MCSO

The Good Night John Boy incident and subsequent response have drawn ire from several former members of Manatee County agency, saying it has created division between ranks and squashed morale.

Several former deputies reached out to reporters in late October, upset about what they viewed as a double standard. Some current and former members of the department also took to Facebook, criticizing the agency’s handling of the incident. Only one of them went on the record. Others said they feared retaliation for speaking out.

Many pointed to other cases where lower-ranking members of the department faced stiffer punishments for what they claimed were minor offenses with no victims.

Among them was retired SWAT Commander Tim Downey Sr. He said he was suspended for four days without pay for removing spent shell casings from a firing range and selling the brass to buy T-shirts for members of his team.

Another one, Sgt. John Finley, resigned from the department in 2021 after facing discipline for detonating a flashbang to announce his arrival at a party, according to news reports. Flashbangs are explosive devices used by law enforcement to disorient barricaded suspects in dangerous situations. No one was hurt.

Suncoast Searchlight requested the internal affairs documents for seven cases described to reporters but did not receive them by press time.

The Manatee County Sheriff’s Office purports to follow a “progressive discipline system” that emphasizes “a series of increasing sanctions for repeated or multiple offenses” aiming to correct employee performance problems. That includes policies that punish agency supervisors more severely.

However, former deputies who faced discipline at the agency alleged that doesn’t always happen.

Former Manatee County Sheriff’s detective Tara Burge said she was forced out after a decade with the agency over accusations of being in a relationship with a convicted felon and “disseminating confidential information.” Burge told reporters she disputed both allegations and that she had not spoken to the man, whom she described as a family friend, for nearly a year.

Both Porter and Burge’s policy violations had the same punishment range of possible suspensions of five days up to termination.

Burge said the sheriff’s office placed her on paid administrative leave the same day the complaint was filed in November 2022. She said her badge, gun and car were taken.

When she arrived for an Internal Affairs interview, Burge said, the agency planned to fire her and warned that termination would jeopardize her retirement benefits. She resigned the following day.

In December, Burge filed a federal lawsuit against the sheriff’s office alleging discrimination and retaliation. That case is ongoing.

Burge told reporters that, despite once helping save a man’s life who was threatening to jump from the Sunshine Skyway Bridge, her law enforcement career was upended by what she characterized as a baseless internal investigation and unfair treatment inside the Manatee County Sheriff’s Office.

“I wish I had been part of the cool kids club,” she said, “because I wouldn’t have got fired.”

It’s that kind of perception that can erode trust in a law-enforcement agency, experts said.

“The public sees a double standard when they see cases like this, and the rank and file see cases like this,” Mercado said. “These double standards are toxic to the effective management of police departments.”

This project is a collaboration between the Bradenton Herald and Suncoast Searchlight, a nonprofit newsroom of the Community News Collaborative serving Sarasota, Manatee and DeSoto counties. Learn more at suncoastsearchlight.org.

More from Suncoast Searchlight: Sign up for the weekly newsletter