A history of Phillippi Creek flooding casts shadow over Sarasota’s current stormwater woes

By: Josh Salman | Suncoast Searchlight

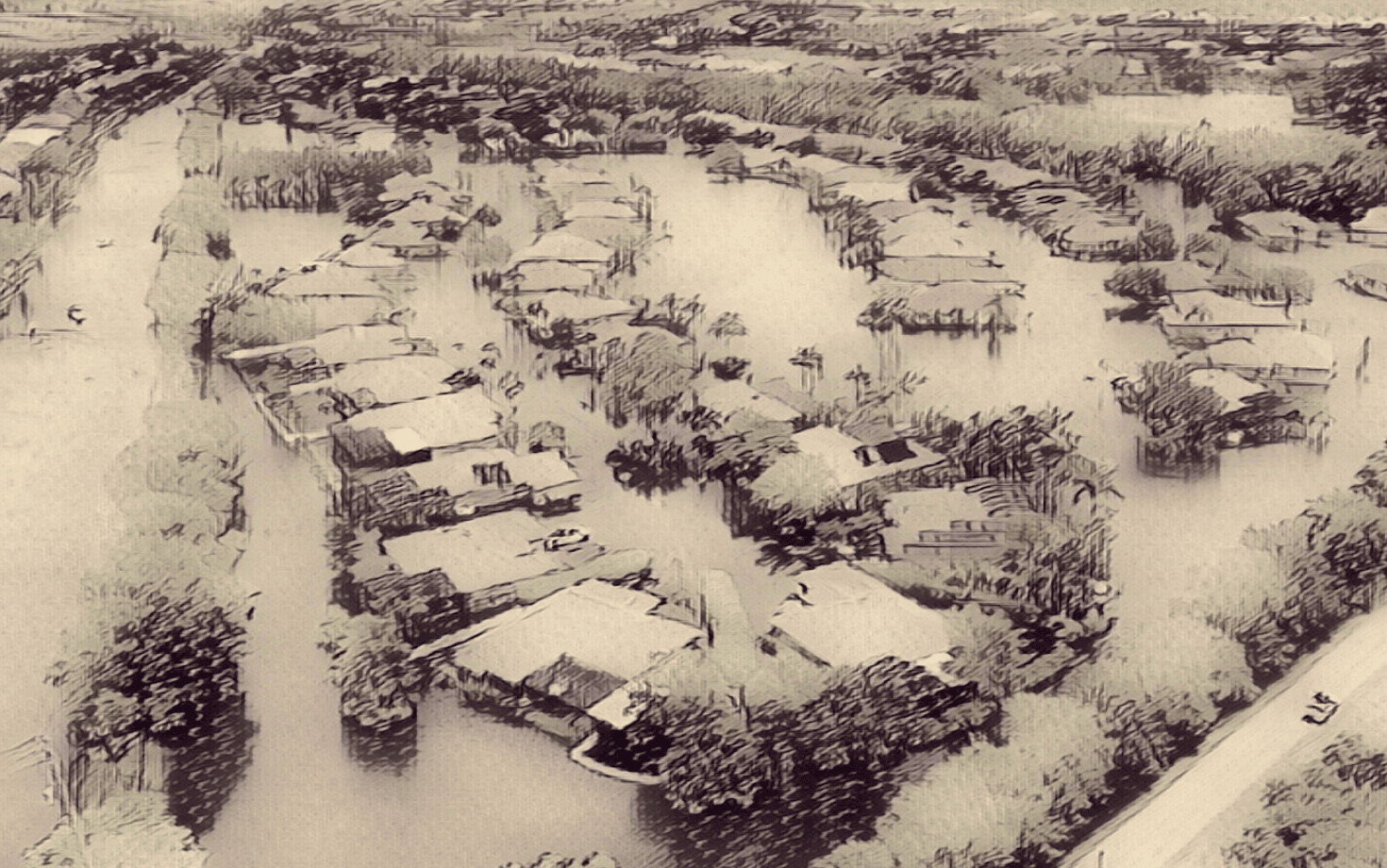

More than three decades ago, residents who lived along Phillippi Creek donned matching T-shirts that read “I survived the Sarasota flood of ‘92” as they packed themselves into the Sarasota County Commission chambers.

They had come to vent frustrations after 14 inches of rain over three days destroyed homes and flooded Bee Ridge Road so high cars could not pass.

County leaders at the time responded by purchasing Celery Fields at the headwaters of Phillippi Creek for flood protection and became the first Florida county with its own stormwater environmental utility to prevent future floods.

The measures were no match for last year’s historic rains that started in June with a tropical weather system called Invest 90L and continued through Hurricane Milton in October.

The downpours were especially devastating as Hurricane Debby tore through the Suncoast in August, wreaking havoc on those same creekside neighborhoods with choppy floods that carried away cars, slapped the roofs of homes and forced longtime residents to seek emergency boat rescues.

The creek spilled out over the bridge at Webber Street. Floods covered stop signs in the Amish-Mennonite community of Pinecraft. The water turned roads to rivers in the Colonial Gables and Laurel Meadows subdivisions.

A Suncoast Searchlight examination of the recent disaster found that county policies in response to the 1990s flood were not enough to keep pace with rapid development in low-lying wetlands that funneled more and more runoff into a creek never properly maintained – replaying a near identical scenario from the three decades prior.

“The creek is not being maintained,” said David Scott, whose home on Mineola Drive in Southgate came just inches from the flooding. “All of the drainage flows into Phillippi Creek, and with it comes sand, muck and debris.”

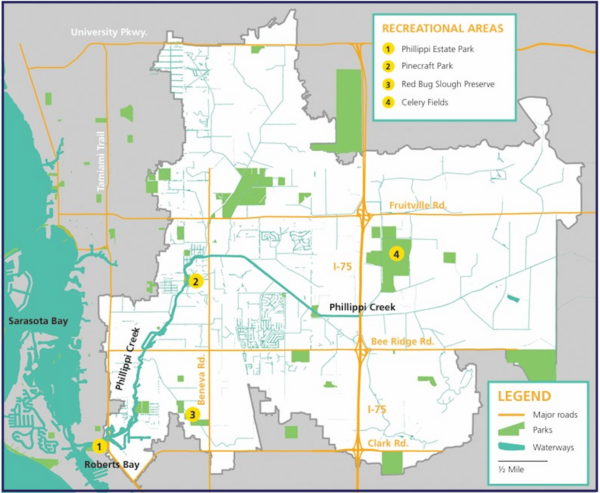

A watershed is an area of land over which rain water flows before collecting in a waterbody. The Phillippi Creek Watershed is highlighted below in white | Map provided by the Sarasota Water Atlas and USF.

Phillippi Creek is the most populated watershed in Sarasota County, spanning more than 55 square miles of neighborhoods from south of Clark Road to north of University Parkway.

Through these subdivisions, a maze of more than 100 miles of man-made canals all funnel runoff into the 7.2-mile creek, which opens near Roberts Bay, then cuts through backyards and commercial centers upstream to Celery Fields east of Interstate 75.

When the system jams – and heavy rain pours down – Sarasota floods.

The creek contributed to major flooding in the region 60 years ago. Then again in the early 1990s. Dozens of residents whose homes flooded last year insist the storm surge would have drained from their neighborhoods much sooner – saving their homes from destruction – had the creek not been left to deteriorate.

Phillippi Creek is tidal, so its waters rise and fall. The freshwater creek has not been dredged in more than two decades, and over the years, it has filled with sediment from erosion.

New sandbars and islands now impede the natural flow of water. Side channels are silted. Banks are falling in.

Broken tree limbs, storm debris and even trash prevented excess flood water from finding its way out.

“Every time it rains, we get more silt,” said Alec Jerrems, who has lived in the same Palos Verdes Drive home for 50 years that sits directly on Phillippi Creek. “The creek is really a mess. There’s just so much debris. There are places you can walk halfway across the creek without getting your shoes wet. Even at the deepest parts, you don’t get your knees wet.”

Sarasota County administration contends it has made stormwater a priority, investing more than $90 million over the past three decades to address area flooding.

The county has sophisticated data on every pond, ditch, and swale, along with rainfall and flooding metrics down to the street-level. But the current stormwater infrastructure was based on climate projections from 1996 – never designed to exceed more than 10 inches of rain. Debby alone brought nearly double that.

Abbey Tyrna, executive director of the advocacy organization Suncoast Waterkeeper, lives near Phillippi Creek and said soil from neighboring properties has filled in the creek. “It’s a real issue,” she said. | Photo by C. Todd Sherman for Suncoast Searchlight

County officials said during a meeting in late February they will pursue a project to dredge Phillippi Creek upstream to Beneva Road. But there is no timetable for the initial $60 million cost estimate presented to county commissioners and some question the source of funding.

“When you get that kind of rain, it’s not something we designed our infrastructure to handle,” Sarasota County Public Works Director Spencer Anderson said. “When you get big rain events, these places flood, especially the plains of Phillippi Creek.”

The fallout from sediment buildup spreads beyond flood protection, and the natural habitat of Phillippi Creek has long suffered.

Pollution from fertilizer, septic system failures, pet waste and stormwater runoff have spiked nutrient and bacteria levels in the creek – all harmful for fisheries and native wildlife.

“It was chock full of algae last year – it’s pretty depleting,” said Abbey Tyrna, executive director of the advocacy organization Suncoast Waterkeeper. Tyrna also lives off the creek. “We all have soil leaving our property and going into Phillippi Creek. You can see the sedimentation, and it’s a real issue.”

Tens of thousands of homes built in low-lying areas face flooding risk

While natural elements of Phillippi Creek date back more than 2,000 years to the native Manasota tribes, most of its history served as a humble farming creek.

The creek was first dredged in 1910 when the owners of 40 acres now known as Phillippi Estates Park were planning a new subdivision. In the 1920s and 1930s, farmers dug ditches and canals upstream of Beneva Road for agriculture, according to research from New College of Florida and Phillippi Park historians.

“When these wetlands get drained for agriculture, they are not wetland anymore,” said Steve Suau, an independent stormwater engineer who previously led the county stormwater department and put together recommendations from last year’s floods. “It gives people a false sense of security that you can build on it.”

As the area became prime for more housing – and the county’s population boomed from just shy of 13,000 people at the start of the Great Depression to nearly 77,000 three decades later – developers converted large swaths of the agricultural land along the creek to residential and commercial properties.

Real estate developers built more and more new ditches to channel runoff from these developments into Phillippi Creek.

When the first major flood struck in September 1962, Sarasota County suffered about $2.3 million in damages in Phillippi Creek Basin, including $1.4 million to private property like homes and automobiles. In today’s dollars, that equates to $24 million in damages overall, including $14.6 million in private property damages.

Dubbed at the time as “the worst storm in nearly half a century,” at least 1,000 homes were inundated by waist-deep water from the nearly 17 inches of rain, according to historical newspaper archives.

When the next “100-year” flood hit in June 1992, hundreds of homes were damaged by the floodwaters that pumped into area rivers. One Sarasota homeowner at the time told reporters “we’ve got the biggest swimming pool in the state of Florida.”

Then in November 1997, parts of the Phillippi Creek watershed were again inundated by flooding – this time, 10 inches of rain fell over a period of 30 hours.

In the decades since, the county purchased Celery Fields, which removed more than 200 homes from an active floodplain, and established its own stormwater environmental utility.

As the Sarasota area became prime for more housing, developers converted large swaths of the agricultural land along Phillippi Creek to residential and commercial properties. | Photo by C. Todd Sherman for Suncoast Searchlight

But the population grew again during that time – from 300,000 people in the early 1990s to more than 470,000 today.

That put a strain on stormwater utility, which now is tasked with maintaining 772 miles of roadside ditches, 252 miles of canals, 305 lakes or ponds and 428 miles of stormwater pipes on a $27.3 million annual budget.

At least one hundred miles of those ditches drain into Phillippi Creek, which serves as the tree trunk of the area’s flood drainage system, with canals that branch off into scattered subdivisions sprawling throughout the county.

Suau said he was stunned to learn the recent state of the creek.

He said the state was intent a century ago on “draining the swamp” in places like Celery Fields, so they could grow crops in the fertile wetlands. Now, up to 80% of the channels and streams in the watershed are man-made.

“One of the big problems is that it has been over 30 years since we’ve had that type of flooding, and people forget,” Suau said.

There are more than 120,000 properties in Sarasota County at risk of flooding during the next 30 years – about half all properties in the county, according to data from the First Street Foundation.

David Tomasko, executive director of the Sarasota Bay Estuary Program, said the problems stem far beyond creek maintenance. As the watershed expanded over the years through man-made streams, climate change has brought warmer weather and intensified storms.

“The biggest issue is the creek has very little natural elements – there’s almost nothing natural about the watershed,” Tomasko said. “It has been ditched and dammed for decades … You have an urban creek in Florida that just went through four big (rain) events.”

Sand, silt and debris: Flooding rocks creekside neighborhood

Jacob Crabtree’s home was destroyed by surging water when Hurricane Debby tore through the Suncoast in August.

For five years, he lived north of Proctor Road on a cul-de-sac overlooking the main channel of Phillippi Creek. As Debby dumped nearly 18 inches of rain in just hours, a sea of stormwater that typically drains into the creek instead overtook his peaceful street.

Still unable to move back in, Crabtree has been displaced for more than six months. The damage triggered new federal flood zone rules, so before he can begin to rebuild, the entire house must be lifted, costing him hundreds of thousands of dollars.

He has no clue what to do next – and he blames the devastation on a lack of proper maintenance to Phillippi Creek.

“Almost all of the stormwater from the (area) funnels into Phillippi Creek in some shape or form,” Crabtree said. “You’re putting all of this water into one basin.”

Crabtree was among dozens of Phillippi Creek residents who spoke out at a county commission stormwater workshop in January and a Tiger Bay luncheon in February to voice dismay over last year’s floods and how they believe a lack of proper maintenance played a major role.

New sandbars and islands now impede the natural flow of water in Phillippi Creek. Side channels are silted. Banks are falling in. Broken tree limbs, storm debris and even trash prevented excess flood water from finding its way out. | Photo by C. Todd Sherman for Suncoast Searchlight

If sediment is near the water line, experts say that limits the volume or moving capacity of the creek. When heavy rain pours down, the water floods in place instead of exiting out to the bay.

“We maintain our ditches – and we treat Phillippi Creek like a ditch – so why are we not maintaining it?” Crabtree said.

Following Debby in early August, the water levels of Phillippi Creek near the Bahia Vista bridge topped 10 feet – the highest in more than two decades, according to the Sarasota County Water Atlas data dashboard. Other areas of the creek were measured as high as 25 feet.

Although Scott’s home on Mineola Drive in Southgate was spared from the flooding, his parents, who live directly across the street, were not as fortunate. They saw 6 inches of water gush inside their house, forcing them to replace appliances and gut rotten drywall.

Scott grew up on the creek and has seen it evolve over the years. He loved watching giant manatees float right through his backyard, but they don’t come around anymore. He thinks the creek is too eroded.

“The creek is not being maintained,” Scott said. “All of the drainage flows into Phillippi Creek, and with it comes sand, muck and debris.”

Jon Thaxton, the Gulf Coast Community Foundation’s senior vice president for community leadership, who served as a county commissioner years ago, supports creek dredging.

But he questions the funding sources under consideration and said the real problem lies with a lack of basic maintenance between major dredging projects. Thaxton said dredging will only help with flooding from rainfall and not coastal storm surge.

“No doubt homes flooded as a result of a lack of maintenance to Phillippi Creek,” Thaxton said. “But the real question is how many of the homes that flooded would not have if the creek was dredged? Are we looking at that?”

“Right now, we are expecting an 8-ounce cup to hold 10 ounces of water, and it doesn’t work.”

Officials scramble to dredge the creek

Phillippi Creek was last dredged in 2002 from the mouth near the bay up to Tuttle Avenue.

At a cost of $1.3 million, crews excavated 59,000 cubic yards of material, dredging an opening of about 20 feet by 5 feet – just enough for a boat to get through – but not up to the banks.

Inland dredging, including Phillippi, is led by the third-party West Coast Inland Navigation District, which has its own countywide mileage rate to fund projects.

WCIND has a project on the books to again dredge the creek, this time to U.S. 41, just near the mouth. There’s no timetable for the project, estimated to cost between $1.7 million and just over $2.3 million.

Anderson, the county’s public works director, said the county will try to work with WCIND to find a way to dredge further upstream to Beneva Road.

County commission agreed in late February to set aside $75 million of the $210 million federal HUD Resilient SRQ grant for hurricane housing recovery towards waterway dredging, including Phillippi Creek.

Thaxton, the former commissioner, argues that more of the money should be spent on affordable housing as intended by HUD. He points to two other funding sources – including the Navigable Waterways Maintenance program – which can create special assessment zones for addressing the creek.

WCIND now plans to dredge up to near U.S. 41, pointing to general public interests, like Phillippi Creek Oyster Bar, a waterfront restaurant. The agency’s test for a “public waterway” is that a public person on a boat can go there – like a restaurant, marina, boat ramp or waterfront park.

The agency determined upstream Phillippi Creek had no actual public benefit for general boaters – just the private homeowners who live there.

WCIND Executive Director Justin McBride said the project has yet to go out to bid for contractors, but he hopes to have his agency’s scope of work completed by early next year.

“Our interest is purely in restoring navigation,” he said. “But that doesn’t mean the county can’t piggyback off our concepts.”

As stormwater dumps in, creek water quality suffers

Phillippi Creek was long considered a hotbed for wildlife like otters, snook, osprey and manatees.

But all the floodwater across the county dumping into the ecosystem has taken a toll on those natural habitats.

Sediment packed with heavy metals and petroleum has tainted the water. Runoff has elevated nutrient and bacteria levels. And high turbidity, which gives the water a darker look, has stripped away the oxygen available to aquatic life.

Phillippi Creek was long considered a hotbed for wildlife like otters, snook, osprey and manatees. But all the floodwater across the county dumping into the ecosystem has taken a toll on those natural habitats. | Photo by C. Todd Sherman for Suncoast Searchlight

Water samples taken by the University of South Florida Water Institute found the quality of the creek to be “poor” through much of 2023 and 2024 based on sediments, nutrients, temperature, contaminants and the amount of dissolved oxygen in the water.

The creek is now designated as “impaired” by the Florida Department of Environmental Protection, which evaluates aquatic life, recreation use, and the ability to consume fish and shellfish.

Residents and organizations in the Phillippi Creek Watershed have partnered with Sarasota County on an initiative to improve water quality in the creek.

Working with area homeowners, the county converted more than 8,000 aging septic systems and 32 small wastewater plants into a more modern sewer system. That alone translated into almost 9 million gallons of wastewater per day no longer discharging into the watershed, according to county documents.

The county uses two “sediment sumps” upstream of Bahia Vista Street to collect the buildup to prevent it from going downstream.

The county also has a capital project on the books for stream restoration and bank stabilization to reduce nutrient loads and prevent further erosion to the creek’s northwest tributaries. Construction costs have yet to be determined, but the county estimates $593,730 for the project’s design.

Environmentalists say the efforts are not enough. They said dredging should ease the storm drainage concerns, but also worry it could still pose a negative environmental impact, especially in the short-term. The large machinery digging up sediment can also eat up biological life, including helpful bacteria.

“Phillippi Creek is a law of unintended consequences when you develop a watershed,” said Glenn Compton, chairman of the local environmental advocacy group ManaSota-88 Inc. “The sedimentation is the result of an urban landscape. You are going to have water quality issues, and water quality in the creek will have a big impact on water quality in its receiving waters.”

Josh Salman is deputy editor/senior investigative reporter for Suncoast Searchlight, a nonprofit newsroom of the Community News Collaborative serving Sarasota, Manatee, and DeSoto counties. Learn more at suncoastsearchlight.org.

ABOUT THIS PROJECT: Suncoast Searchlight is partnering with the nonprofit Florida Trident and its publisher, the Florida Center for Government Accountability, to examine the challenges facing Florida as it grapples with hurricanes, sea level rise and climate change. This story is part of that statewide effort.